Over summer, I’ve been experimenting with more autonomous coding agents. In our work at Icehouse Ventures, I basically read every line of code that we commit to production and we optimise heavily for security and stability. We do use a lot of AI tooling, but we keep it on a much tighter leash than a lot of the looser modern tech teams working on consumer software. I find that the Kiwi summer holidays are a perfect time for some light side-projects and exploring new trends. One thing that’s come up a lot during the last year and seems to be accelerating is the ability of coding agents to make large scale changes to a large scale code base. By themselves these create a bit of review problem, but when several large scale refactors collide things can become irreconcilable.

Git isn’t powerful enough to keep up with Agent Swarms

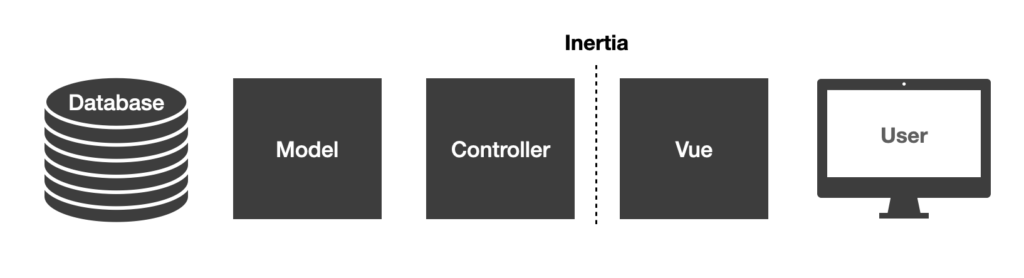

Steve Yegge’s recent piece on AI agent swarming raised a concept that’s been rattling around in my head for a while: the “Merge Queue” problem. If you’re running multiple coding agents in parallel Cursor, Claude, Gemini, whoever… you’ve probably already felt this pain. Each agent starts from the same baseline, does meaningful work, the peer-agent code reviews make sense, but when it’s time to merge… chaos. The codebase has shifted so dramatically in the meantime that a normal merge or even a rebase before merging is no longer feasible. As Steve puts it:

“When the fourth agent D finishes its work, a rebase may no longer be feasible. The system may have changed so much that D’s work needs to be completely redesigned and reimplemented on the new system baseline.”

This got me thinking. We’ve been using the word “rebase” to describe a mechanical git operation. But what we actually might need, especially in the age of AI-assisted development, is something more expansive. We could call it a Semantic Rebase.

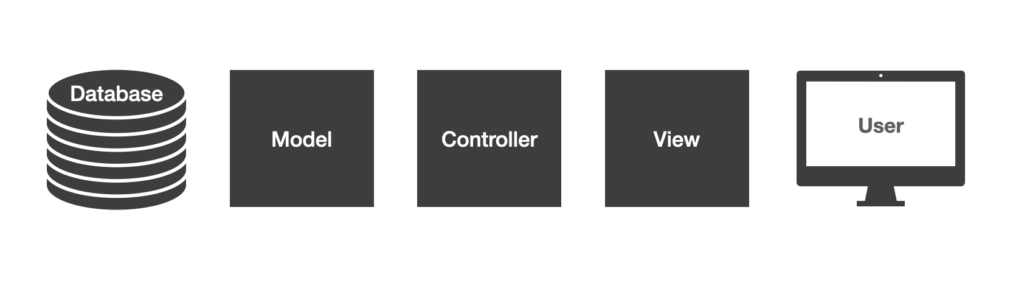

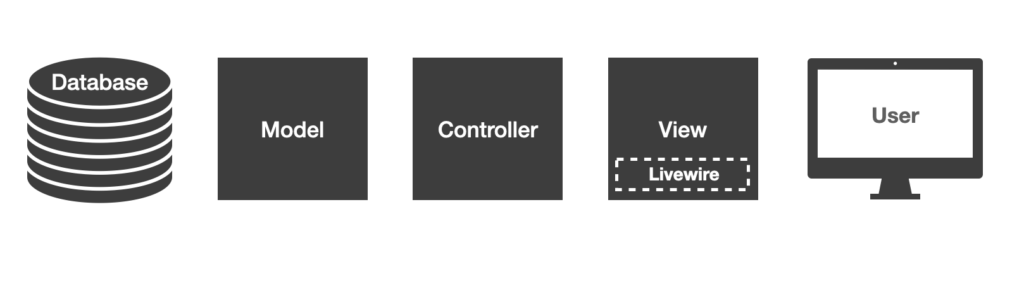

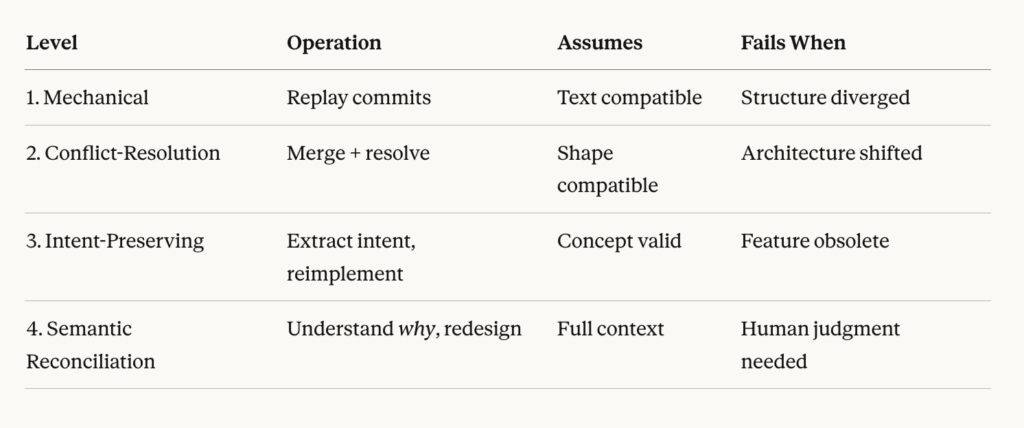

Level 1: Mechanical Merge (Simple Rebase)

This is what git rebase actually does. Replay commits onto a new base. It works beautifully when your changes are textually compatible with the new baseline—when the files you touched haven’t fundamentally changed.git checkout feature-branch

git rebase master

Assumes: Your changes are additive. The code you modified still exists in roughly the same shape.

Fails when: Someone restructured the module you were working in. Your commits literally can’t apply.

Level 2: Conflict-Resolution Rebase

This is what most developers do when Level 1 fails. You merge, you resolve conflicts, you move on. IDEs are helpful here. You’re still operating at the textual level, but with human judgment applied to conflicts.

Assumes: The shape of the code is still compatible. The architecture hasn’t fundamentally shifted.

Fails when: Your branch assumes a certain directory structure, API pattern, or architectural approach that no longer exists in master. You’re not just resolving conflicts—you’re trying to fit a square peg into a round hole.

Level 3: Intent-Preserving Reverse Merge

Here’s where things get interesting. At this level, you stop trying to mechanically merge code and instead ask: what was this branch trying to accomplish?

You extract the intent of the feature, then reimplement that intent on the new architecture. Personally, I sometimes do this manually by merging master into the feature branch before trying to do a PR. It can be a bit impolite doing this type of “reverse merge” onto a human’s code as you’re effectively taking over their code, whereas an agent doesn’t mind.

This is fundamentally different from Levels 1 and 2 because you’re doing:code₁ → intent → code₂

Rather than:code₁ → code₂

The original code becomes reference material rather than source material. You’re not replaying commits—you’re rescuing functionality.

Assumes: The feature concept still makes sense in the new architecture.

Fails when: The architectural changes have made your feature obsolete, or the approach fundamentally incompatible at a conceptual level.

Level 4: Semantic Rebase (Reconciliation based on Meaning)

This is the hardest case, and the one Steve flags directly: “What should we do if Worker A deleted an entire subsystem, and Worker B comes along with a bunch of changes to that (now-deleted) subsystem?”

At Level 4, you need to understand not just what changed, but why. Maybe Agent A deleted that subsystem because it was replaced with something better. Maybe Agent B’s changes should now target the replacement. Or maybe Agent B’s work is simply obsolete and the problem it solved no longer exists.

This requires genuine understanding of both the old and new systems. It’s the level where human judgment (or very good AI judgment with full context) becomes essential. A semantic rebase doesn’t merge the code, it merges the meaning.

Why This Matters Now

For most of software development history, mechanical merges and rebases were sufficient. Teams worked on separate features. Branches lived for days, not weeks. And if they did become a dreaded “Long Lived Feature Branch”, you could periodically merge master into the feature branch to keep the home fires burning. The codebase didn’t shift that dramatically between branch creation and merge.

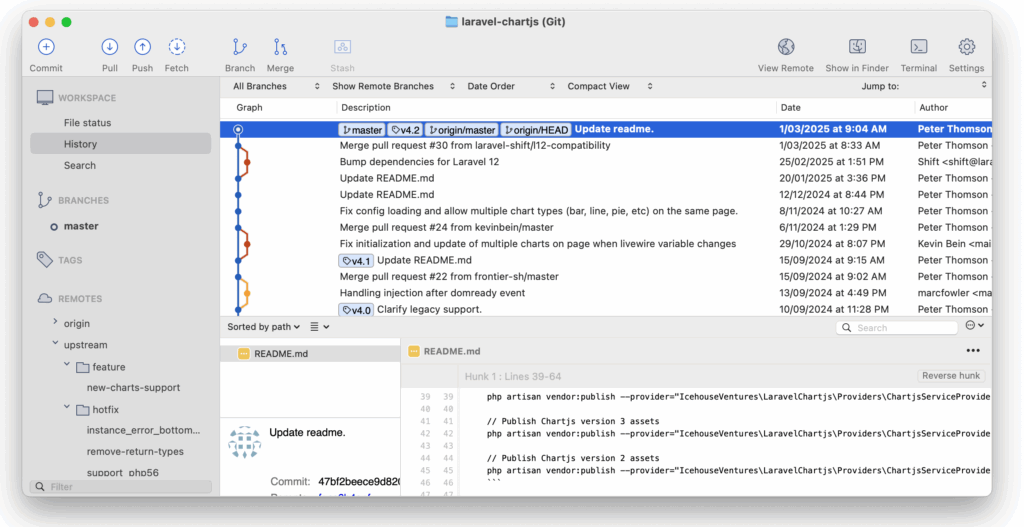

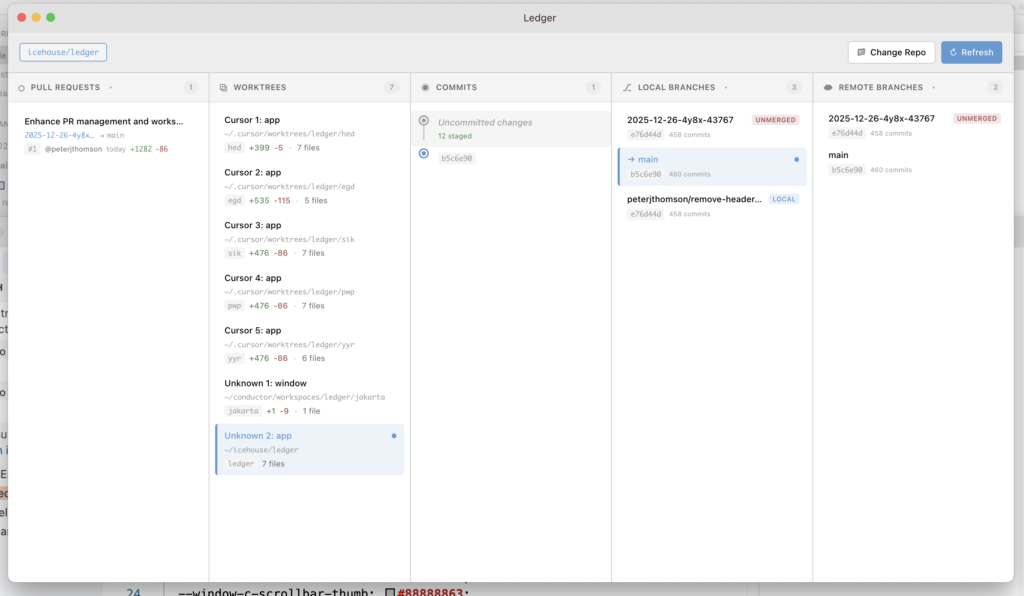

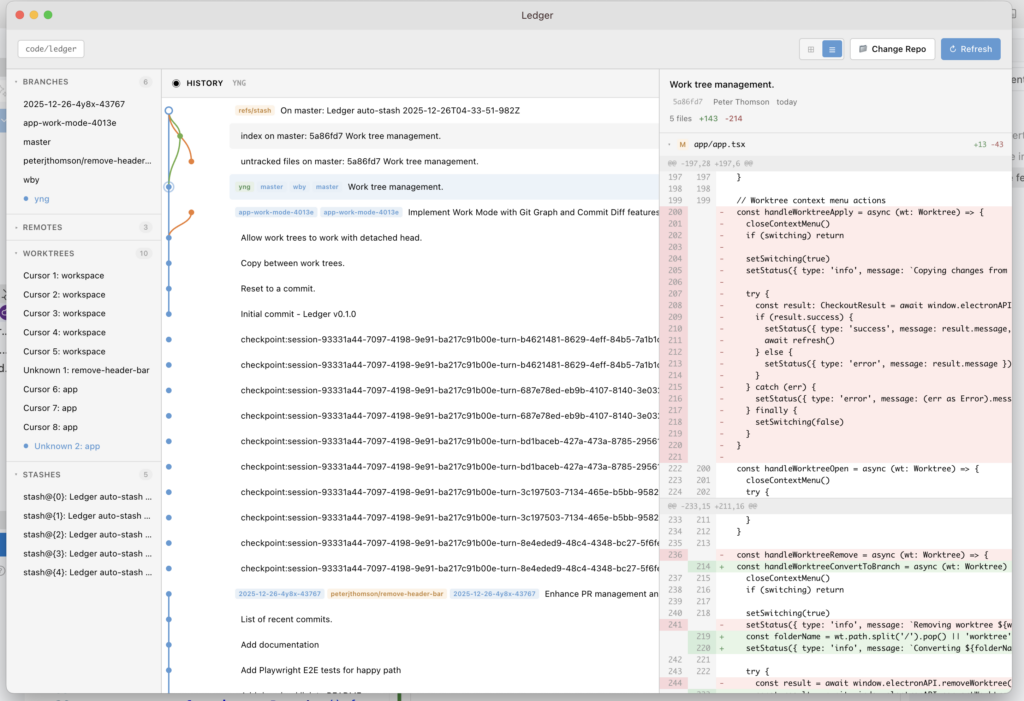

AI agent swarms change this equation entirely. When you have three, five, or ten agents working in parallel, each capable of making sweeping changes, the probability of deep structural conflicts goes up exponentially. This summer, I’ve been building an open source experiment in advanced source control tooling partly because I needed visibility into this exact problem: what are all my agent worktrees doing, and how badly are they about to collide?

The traditional git model assumes one canonical history that everyone’s rebasing onto. The swarm model creates multiple divergent histories that all need to converge. That’s a fundamentally different problem.

The human-in-the-loop

Yegge predicts the rise of the “superengineer”, someone who can orchestrate 100 coding agents and get meaningful work done with them. I think he’s right, and I think things like rescuing or reconciling divergence among agents (through things like a Semantic Rebase) will be one of the core skills that separates effective agent orchestrators from everyone else.It’s not about being better at resolving git conflicts. It’s about recognising when mechanical rebase is futile and switching to intent-preservation mode.

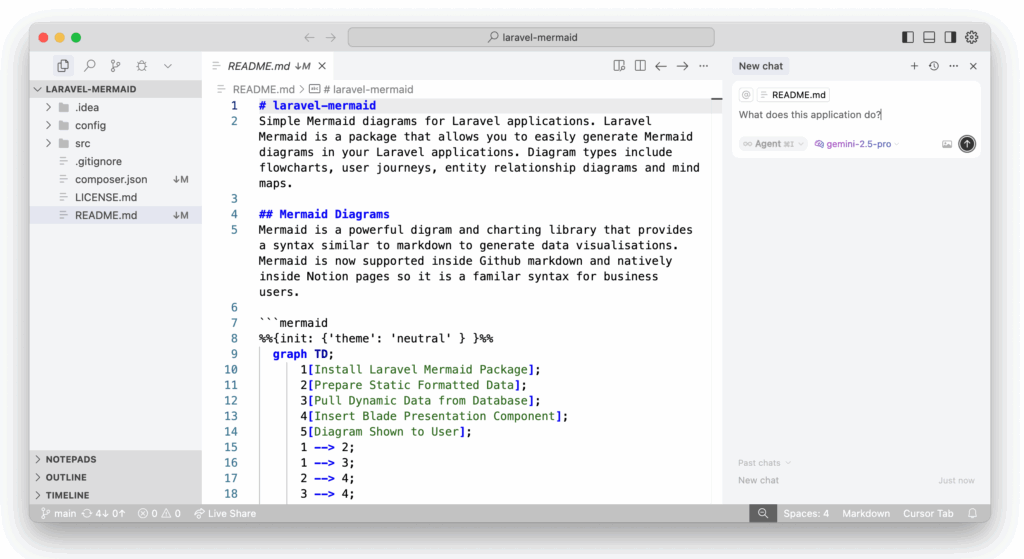

Something I’ve found helpful for codifying the semantic intention behind the code is “domain tests” and putting our documentation inside the repository so there’s a shared understanding between users, developers and agents.

Extracting intent from code (reading comprehension at scale exactly the skill Yegge says is “draining and beyond the capabilities of most devs”). Reimplementing efficiently on the new baseline, leveraging the new patterns rather than fighting them. Then making judgment calls about what to rescue and what to abandon.

This is, ironically, a task that the latest generation of AI agents are well-suited for: understanding intent and reimplementing, which suggests the solution to the “merge queue” problem might be… more agents. But specialised prompts, skills or sub-agents with reconciliation focus that understand both branches and can perform a “semantic rebase” themselves.

Tooling Gaps

Current git tooling is entirely built for simple code reviews and mechanical merging. git rebase, git merge, even fancy visual merge tools, they’re all operating at the surface textual level. What we need for semantic rebasing to work:

1. Branch intent extraction: What was this branch trying to do? (Commit messages help, but agents don’t always write great ones)

2. Architectural diff visualization: Not just “these files changed” but “the module structure shifted from X to Y”

3. Conflict severity assessment: Is this a Level 1 conflict or a Level 3 conflict? Should I even try mechanical rebase?

4. Intent preservation tracking: When I reimplement a feature, how do I verify I preserved the original behavior?

I’ve been experimenting with some of this in an open source experiment in visual source control, at minimum, being able to see which agent worktrees have diverged and by how much helps you prioritise what to merge first. But the deeper tooling for semantic rebase or “merging meaning” is still nascent across the industry.

Borrow this Prompt

Until better tooling exists, here’s a prompt I’ve been using when I need to perform a semantic rebase. It works well with Claude Code, OpenAI Codex, or similar capable agents that have access to your codebase:

Reconcile this feature branch with master so it can be merged cleanly. Do not change master, only this feature branch. Warning, master has undergone significant structural changes, so this isn't a simple merge from master to reduce the diff. Suggested approach:

1. First, assess the scope — compare this branch against master to understand what's diverged in both.

2. Merge master into this branch.

3. Resolve conflicts, prioritizing master's architecture where there are structural disagreements.

4. Rebuild/rescue feature functionality to work within master's current patterns.

5. Verify the feature still works as intended.

The goal is a PR that:

- Has no merge conflicts with master.

- Follows master's current architectural patterns.

- Preserves the feature's intended functionality.

Note: If the divergence is too severe, it may be faster to cherry-pick the feature's intent onto a fresh branch from master rather than wrestling with conflicts.The key insight in this prompt is step 4: rebuild/rescue. You’re explicitly giving the agent permission to abandon the original code in favor of reimplementing the intent. And the escape hatch at the end acknowledges that sometimes even Level 3 rebase isn’t worth it, sometimes you need to start fresh with just the intent.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Steve is skeptical that we’ll get guardrails that make this accessible to “average” developers. I share that skepticism. Semantic rebase requires the exact skill that’s hardest and most draining: reading and understanding large amounts of code, in multiple versions, and making judgment calls about what matters.

The developers who get good at this, who can look at a hopelessly diverged branch and quickly extract its intent, assess the new baseline, and reimplement efficiently, are going to have an enormous advantage. It’s not just about prompting. It’s about understanding codebases at a level where you can direct agents effectively.

The swarm is coming. The merge queue is real. And “rebase” is about to mean something much more interesting than git rebase.

I’m making a desktop app for managing Git repositories with AI agent worktrees open source and available for free on Mac, Windows and Linux. If you’re running multiple coding agents and want visibility into what they’re all doing, check it out.