Company valuation is one of the most misunderstood parts of early stage investing. Both investors and entrepreneurs get themselves endlessly tied in knots trying to calculate a startup’s “value” despite the fact that the whole concept of valuation is entirely artificial. How to value a startup is one of the most common questions I get when I present to entrepreneurs on the topic of venture capital and online angel investing. What worries me the most is that talking about valuation in isolation can distract people from the real issues of economics (amount of cash invested) and control (percentage equity offered).

One of the most common questions that you hear entrepreneurs and VCs ask each other is “What’s your valuation”? It seems like a sensible question and it’s a tempting way to compare different companies who are raising capital, but the idea of a single number as an agreed valuation for a startup is a dangerous distraction from the real issues. The term “valuation” is simply a useful shorthand to talk about several independent variables. These variables can be quickly forgotten when you start a conversation with the issue of valuation.

Unbundling the components of valuation

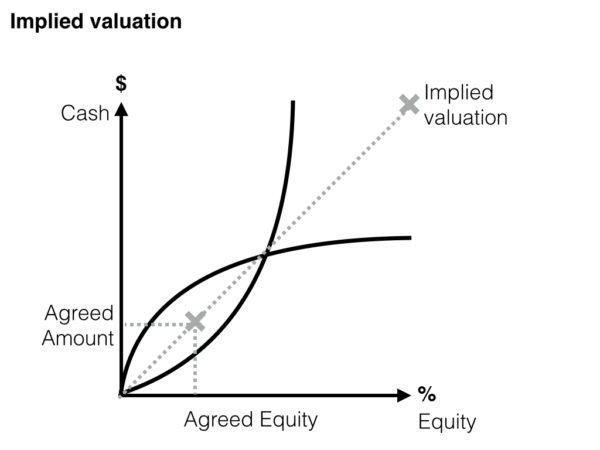

In the world of startup finance, when we talk about valuation we’re generally talking about a single number that summarises the current round of finance. This valuation is a mathematical calculation of the total value of the company based on the percentage equity that changes hands and the amount paid for that equity. The theory is that if an investor pays a certain price per share, for a certain number of shares in the company, then the total value of the company is simply the total number of shares outstanding multiplied by the price per share. The logic behind this calculation is that if all the shares are equal, then they are all worth the same amount, and the value of one part of the company can be used to infer the value of the rest of the company. This logic is one of the great unexamined myths of startup finance. And I’d argue that this valuation myth blinds us all to the real dynamics of startup finance.

The real issues in startup funding are the two variables that are used to calculate valuation:

- Cash (Economics): How much are is the investor paying for the shares?

- Equity (Control): How many shares are being issued to the investor?

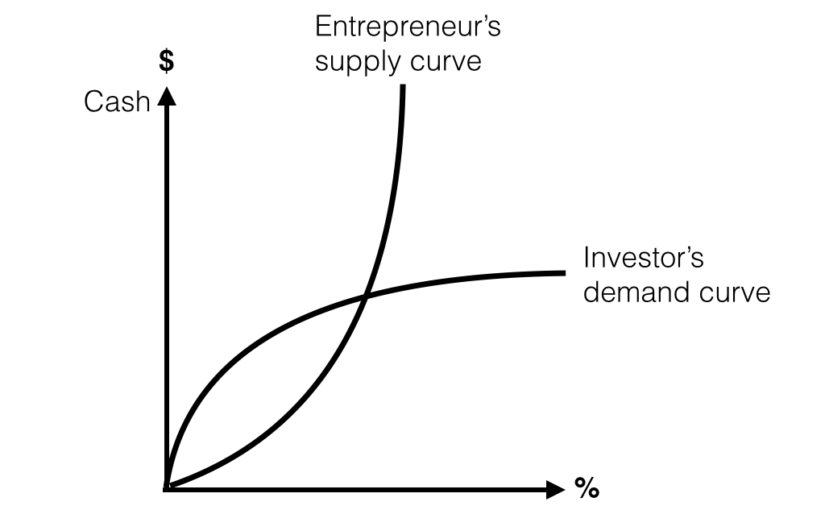

Each of these variables have complex supply and demand dynamics that play into the end transaction. Some of these dynamics appear irrational until you break down the motivations of each the players individually.

My experience is that the different motivations for entrepreneurs and investors mean that there really isn’t really such a thing as a single company valuation that can be calculated, because neither party really believe that the single value implied by a one-off transaction is the real value of the company.

When I say that there is no such thing as valuation, what I mean that is that the fact that an investor and entrepreneur can do a deal for a particular amount of money (in return for a particular amount equity), doesn’t actually mean that either of them would agree to sell (or buy) the whole company at the valuation that would be implied from their one-off transaction.

The myth that the price of a part tells you the exact price of the whole is sometimes true in the world of private equity where whole companies are bought and sold, or in the public markets where the market cap is floating and management control is separated from investment economics. But even then, large voting blocks that can used to either force or block a takeover can still be worth more or less than the average price per share of the rest of the stock in the company.

To understand how a startup valuation really works we need to examine the supply and demand drivers balancing out the transaction.

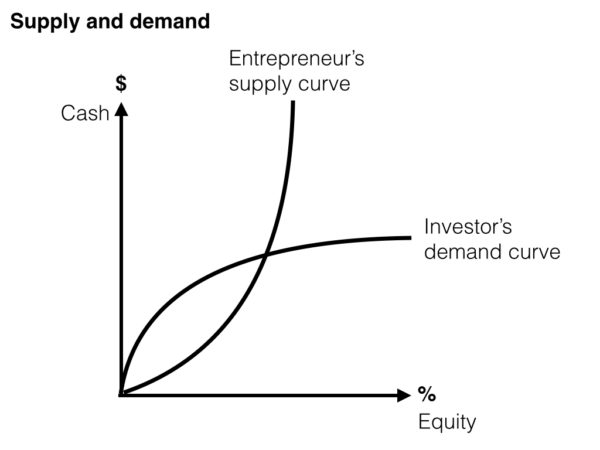

Percentage equity

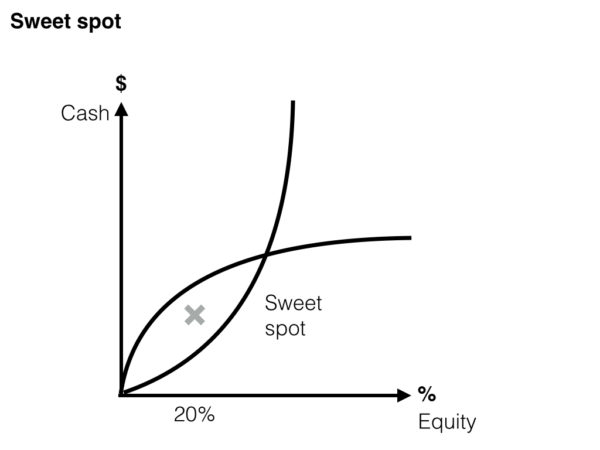

The percentage equity for an early stage financing round tends toward an average of around 10% to 30% because the various supply and demand factors balance each other out. When the equity offered is too low, the investor feels that they aren’t getting a large enough ticket to the races. Likewise, the entrepreneur knows that they should be offering more equity to attract good quality investors and to avoid overpricing the company too early.

On the other hand, when the equity offered is too high in any given round, the investor worries that the entrepreneur will become less incentivised to make the company a success. And the entrepreneur will also worry that they don’t have enough shares in the company left to account for future rounds of capital.

The percentage equity in a funding round tends to be in a stable range, so the real variable in negotiating a transaction is the amount of cash paid for the equity that’s on offer. The cash price of the equity is subject to some interesting psychology and economics. This is the real battlefield of negotiating a startup financing round happens.

Entrepreneur supply of the shares

On the entrepreneur’s side, the fact that you’re willing to sell a fraction of your company now (because you need the money), doesn’t actually mean that you would be willing to sell the whole company at the same share price. In your mind, the business has massive potential and you’re dedicating your life to it. You’re willing to accept a lower valuation right now, because you know that the cash will help you grow.

Investor demand for the shares

On the investor’s side, the fact that an investor is willing to buy a fraction of your company now doesn’t mean that they would be willing to purchase the whole company outright for the same share price. In their mind, they’re in the game to place small bets into multiple startups, and not acquire whole companies (which would involve installing their own management team and running the company). They’re willing to pay a higher price per share for a small stake in your company than they would for the whole company because they want to get the return on investment from all the hard work that you will be doing to grow the company.

Matching supply and demand

When the factors driving supply and demand overlap, then the two parties have a range in which they can do business. If you understand the boundaries of the supply and demand curves, then you know the space in which you can negotiate. A good financing round leaves the investor happy because they’re getting a percentage that they feel good about, and paying a price that they think is fair. Likewise, the entrepreneur is happy because they are ceding a sensible amount of control in the company and receiving a healthy injection of cash to grow the business.

Some investors and entrepreneurs like to negotiate really hard on both the economics and control points but this is a risky game because investing in a startup is like getting married. It’s a long-term relationship and both parties need to be on good terms to maintain the relationship over time. In the parlance of behavioural economics and game theory, startup investing isn’t a one-play game, it’s a multi-play game, so trust and goodwill are vital to a good long-term outcome.

Pre-money and post-money valuation

Most early stage investments consist of a new investor purchasing newly issued stock in the company in return for cash that is transferred to the company (not to the existing shareholders). This is very different to selling your car (or even selling part of your car) because when you sell a car, the car doesn’t open a bank account and keep the money for itself (thereby turning itself into a more valuable car). This is why good investors distinguish between pre-money valuation and post-money valuation.

Pre-money valuation is the total value of the company before the investment and is calculated based on the amount to be invested and the equity to be issued, whereas post-money valuation is the same maths applied to the company after the money has been received and the new shares have been issued. Problems can arise when an informal agreement to invest is based on an agreed valuation without specifying whether the number agreed is pre-money or post-money. The difference between pre-money and post-money can significantly change the economics of the deal. This is another reason why I prefer talking about the tangible factors of economics and control, rather than an implied valuation.

External ways of calculating a company value

The normal corporate finance methods of valuing a company such as net present value, discounted cashflow and comparable companies are useful for coming up with a proxy for the total company value at a time when there are no shares for sale. But during a capital raising for a startup, the external methods for valuing a company distract from the real question of supply and demand for the shares on offer. Sometimes an old-school investor will try to get an entrepreneur to justify their valuation by demanding the creation of one a financial model. My experience is that if an early stage investor wants to use an external justification for the valuation, then they don’t really want to make the investment at all and they’re simply asking you to make their decision easier for them by attacking your assumptions. This changes in later investment rounds when venture capital firms can make useful calculations based on customer lifetime value and the cost of customer acquisition.

Maximising your valuation

Like any market value, the price that you can command for shares in your company is a matter of matching supply and demand. If you can increase the demand, then you can increase the price. The factors that determine investor demand vary wildly between investors, but the common factors usually include traction, market size and management team. Increasing the investor demand for shares in your company is just like increasing customer demand for your product, it’s simply another marketing task.

Rapid valuation shortcut

Sometimes an investor will put you on the spot and demand to know your valuation. These are usually naive investors, but sometimes the factors of valuation (cash and equity) are legitimately necessary for an application to a startup accelerator or to create an equity crowdfunding campaign. The best way to determine your startup valuation in a hurry is to simply ask two questions:

- How much money do I need? That is, what’s the least amount of money necessary to reach the major milestones that will help me raise the next round of capital after this current round?

- How much control am I willing to give up? That is, what’s the most amount of equity that I’m willing to give up at this stage in the company’s life, given that both the new investors and myself are going to be diluted by future rounds of capital?

If you know the minimum cash that you need and the maximum equity that you’re willing to accept, then you know your baseline valuation and everything else is a matter of negotiation.